A cataclysm

My parents are of the ‘smacking’ generation. The further the notion of casual violence against children recedes into the past, the more ridiculous it seems – but throughout my early years it’s a constant threat.

It’s frequent, and usually unplanned. It comes out of the blue. I’m seldom even aware of the crime, but suddenly feel them holding one of my hands high in their left hand, as a rudimentary tether, whilst their right hand swipes indiscriminately at my nether regions.

It’s such an imprecise manoeuvre – perhaps its saving grace – and allows me to squirm about like a badly behaved puppet. This presents a moving target which makes it difficult for them to deliver the killer blow. They want to hear the ‘smack’. Only the sharp smacking sound will convince them that justice has been done. They want to say, ‘Let that be a lesson to you’, and they can’t say it until they hear the smack.

So all my writhing about, all my jumps and side steps, my running round in circles, merely prolong the agony.

It’s hard to know whether standing still and just letting them hit me would make the sorry business end sooner. Part of me fears that if they could get the smacking sound more easily they might just do more of it. So perhaps wriggling about is the best policy.

Dad’s decision to swan off to Uganda comes in January 1969, when I’m turning twelve. He leaves suddenly. On his own. I sometimes wonder if Dad wasn’t running away from something, rather than to something: From his mother? From Bradford? From the Mission? From us?

Because the rest of us – Mum, Hilary, Matthew, Alastair and me – are left in Bradford. We’re to join him in six months. This is supposedly because Hilary is in her final O-level year and it’s considered important not to interrupt her studies.

No one suggests it might be important not to interrupt family life by buggering off to Uganda. No one thinks it might be important not to leave Mum looking after four kids on her own. No one mentions that he’s off to live the life of Riley while the rest of us are off to live in a grim council flat in Thorpe Edge because Dad has already sold the family home in Highfield Road.

While Dad is off on an adventure to equatorial Africa, joining the expat club in Jinja, learning golf, playing squash, and swimming in the outdoor pool, we’re travelling up to the seventh floor in a lift that reeks of Greenland shark, to a landing with an open rubbish chute that stinks of the same shark twelve months later. Whenever the lift breaks down – most days – with me and my younger brothers in it, they both scream in panic and fury like young berserkers in the making.

I don’t know exactly what I say to upset my mum so much on the day Dad leaves for Uganda: I hope it’s something along the lines of ‘what a wanker’, or ‘I shall endeavour for the rest of my life never to treat my own family like this’ – and I have to acknowledge that she’s under great pressure – but I make some kind of twelve-year-old’s version of the above comment and . . . she tries to throttle me.

To be fair, there’s not much ‘trying’ about it to begin with, she gives it a bloody good go. In fact I’d say her chances of success are high and that I might be on my way to Valhalla. She’s got both her hands clamped around my throat and is shaking me so hard that my brain feels like it’s detaching itself from the inside of my skull. This is different to smacking. She’s very angry. Perhaps she’s transferring some of her anger towards Dad onto me. If so, she’s furious with him too, and it occurs to me that she wants to kill him.

Puny twelve-year-old me is no match for this raging grown woman – she seems to have a touch of the berserker about her as well – besides which I quickly begin to feel quite woozy. Is she shouting? Is everyone shouting? I can’t tell. Maybe. Her hands have formed a ligature round my neck and my ears are pumped so full of blood I can only hear my own heart thumping. Then I become aware that her grasp is loosening. Maybe she’s too tired to finish me off. Maybe my siblings have cried out in my defence. Maybe not. But it ends with me being told to go to my room and I trudge off feeling faint though strangely exhilarated. Of course, it’s not ‘my’ room, it’s a room I share with my brothers, and they will follow on and do some casual taunting.

‘Ob La Di Ob La Da, life goes on,’ the group Marmalade are singing in the number one spot at the time, and so it does, though second in the hit parade is ‘Albatross’ by Fleetwood Mac, which might be a more fitting metaphor for the Coleridge fans amongst you.

Six months later we all make it to Uganda, but almost immediately I’m sent back to start at the boarding school in Pocklington in East Yorkshire.

Mum said the plan was for all four of us kids to go to school in Uganda, but once we get there Dad changes his mind. My two young brothers are sent to the local international primary (mostly white), and my sister is enrolled in a correspondence course to do her A-levels, but I get sent to boarding school in England. The first person in the history of my extended family to do this. Years later I summon up the courage to ask why and they mumble something about the standard of teaching not being good enough in Uganda. But surely that’s my Dad they’re talking about? What? He wasn’t good enough? All those colleagues that become his best friends, the Steggels, the Pidcocks – they weren’t good enough either?

It’s obvious in hindsight – he didn’t want me going to a school where I would be the only white boy. It was fine for him to teach black pupils, but not fine for me to be their equal.

My only defence is that I was twelve and had no power, and no learned ability to form an argument. Especially with my dad. I grew up in a house where politics were simply never talked about. Ever. There was never any discussion about left or right, about race, about social justice, about how the economy works, about rich and poor. The News was listened to in silence and then not commented on. I once asked Dad which side he voted for in one of the 1974 general elections and he said it was a secret ballot and that I had no right to know. Which I think meant he voted Conservative. I think when people won’t tell you it always means they’ve voted Conservative.

Of course the other reason they sent me away might be that they just wanted to get rid of me? Maybe I was ‘trouble’?

Either way, it turns out to be the most cataclysmic moment of my life.

My mum still makes the defence that she asked me if I wanted to go, and that I said ‘yes’ – so it was my decision, not theirs. If that’s true it was the only time my opinion was ever sought, or indeed acted upon. Aged eighteen I once told my dad I was ‘off to the pub’, and he said, ‘No you’re not – not while you’re living under my roof.’

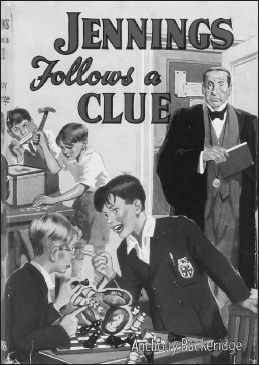

I can imagine that if I was asked I did say ‘yes’. Back in the grotty flat in Thorpe Edge I’d borrowed the entire series of Jennings books, by Anthony Buckeridge, from Eccleshill Library. They follow the adventures of JCT Jennings (only ever known by his surname) at Linbury Court School. They have the same basic set-up as the Harry Potter stories which follow: boarding school, kids allowed their own agency, and lots of japes and scrapes. But Jennings is more parochial, with less wizardry and more jokes. There’s a lot of speaking French incorrectly and setting fire to things – I remember laughing a lot.

So in September 1969, as Creedence Clearwater Revival are top of the charts, rather prophetically, with ‘Bad Moon Rising’, I’m off-loaded at the school by my Aunty Margaret and Uncle Colin, and I cry solidly for two weeks. It isn’t nearly as much fun as Anthony Buckeridge suggested.

The initial scene as they drop me off is a fair enough portent; it doesn’t look at all like the joyful cover of Jennings Follows a Clue. A small seven-year-old boy is screaming ‘No’ at the very top of his voice, and red-hot tears are burning welts down his face, which is a picture of absolute blind terror. Whenever I see a horror film and watch an actor screaming in fright I think back to that kid’s face and remark to myself that actors never get anywhere near it. He’s clinging onto his mother’s wrist while she’s trying to pull away from him. A teacher has hold of the boy’s other hand and is himself hanging onto a cast iron radiator.

A couple of years later I play one of the lawyers in a school production of Bertolt Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle. Two women are in dispute over a young boy: one is his actual mother, who abandoned him as a baby but who now needs him in order to claim some land, the other is the woman who took him in and has cared for him and loved him. The judge draws a circle on the ground, puts the boy in it, and tells the two women to take a hand each, saying that whoever can pull him out of the circle will get the boy. The one who loves the boy fears they will tear him in half and lets go of his hand.

The parallel with the mother, the boy, and the teacher hanging onto the radiator is striking – except in this version the real mother doesn’t want the child, and the school wins. The school always wins. Principally because they’ve got sticks, and they’re not afraid to use them.

My first dormitory is directly opposite Matron Brown’s little dispensary. She’s very kind to me in those first two weeks while I bawl my eyes out. She comes into the dorm and strokes my head and shushes me to sleep. It’s an act of such absolute kindness, and I like to imagine she does it only for me, but she probably does her rounds of the dorms every night at the beginning of each term, soothing all the troubled boys to sleep. And of course, like most boys who are sent to these institutions in the sixties and seventies, I learn to be emotionally cold and maladjusted-without-showing-it-too-much, and finally stop crying.

And that’s the cataclysm really. The definition of cataclysm: a sudden disaster or a violent event that causes change.

It is sudden, and violent, and it does cause change. By the end of my time at Pocklington I have a different accent to the rest of my family and feel I no longer belong. They’re more or less strangers to me. I don’t really know much about them. I go home twice a year – at Christmas and for the summer holidays – and they come back to England once I reach the sixth form, but we share too little time to really connect. And because I’m learning to repress my emotions so effectively, I don’t bloody care!

The only emotions I don’t repress are anger and a desire for excitement that borders on frenzy. I am a novice berserker, and the masters try to beat this out of me. Idiots – little do they know they’re actually beating it in to me.